I acknowledge the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation, traditional custodians of the land on which we meet and pay my respects to all First Nations people here today.

In the minds of many, Ben Chifley is remembered for leading the nation through the end of the Second World War and its aftermath. But he was also the last person to combine the jobs of Prime Minister and Treasurer. Having served as John Curtin’s Treasurer from 1941 to 1945, Chifley kept the Treasury portfolio when he became Prime Minister, serving in both roles from 1945 to 1949. Indeed, Chifley said that he thought he would be remembered as Treasurer and not as Prime Minister (Beazley 2000). According to a journalist of the era, Chifley’s interests ‘were almost exclusively economic and financial’ (Holt 1969).

Chifley’s interest in economics began early. His wife Elizabeth recalled that economic matters were a frequent topic of conversation while they were courting – which suggests he had a better ability to tell economic stories than most of us economists.

Chifley learned his economics during his time in parliament. As he once told Nugget Coombs, ‘I’d rather have had your education than a thousand pounds’. As Chris Bowen has pointed out, Chifley would undoubtedly have gone to university if he’d had the chance (Bowen 2019).

Chifley’s economic achievements were legion. Bowen includes him in The Money Men, his book profiling a dozen Treasurers (Bowen 2015), and notes Chifley’s insistence that Australia choose openness: joining the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, and accepting significant numbers of migrants in the post‑war era (Bowen 2019).

Growing up, I remember conversations in our household about the locomotive driver who became Prime Minister. To a family who believed in social mobility and loved trains, the tale was almost too good to be true. As a university student, my father Michael Leigh had organised the 1963 Ben Chifley memorial lecture at the University of Melbourne (Kennelly 1963). Sixty‑one years later, it’s a pleasure to be continuing the family legacy of honouring Australia’s 16th Prime Minister and 19th Treasurer. My thanks to the Chifley Research Centre and David Epstein for the important work that you do, and to Maurice Blackburn for hosting me today.

Competition brings something better

Chifley spoke about a movement worth fighting for – a movement that brings ‘something better to the people’ including better standards of living (Chifley Research Centre 2020).

Eight decades later, the Albanese Government understands that competition is a proven and effective way of bringing something better to the people.

Competition provides a check on unbridled profit‑seeking by business. In a competitive market, innovators can bring new products and services to market, without fear of being shut down by entrenched monopolists.

Competition limits unearned privilege and seeks to treat everyone fairly. Competition guides labour and capital to their most valuable uses and combinations, driving productivity that underpins sustainable wages growth.

Competition is also about giving Australians more choice.

For workers, genuine competition between businesses provides greater opportunities to switch jobs, allowing workers to make the most of their skills and secure better pay and conditions.

For consumers, competition provides more choices, allowing people to shop around and find better value products and services. Indeed, the most obvious benefit of competition is in delivering cheaper prices. There is no better tool than competition policy for keeping real prices down.

Competition is also crucial if Australia is to make the most of the big shifts around digitalisation, growth in the care economy and the net zero transformation.

Yet there are worrying signs the intensity of competition has weakened over recent decades with evidence of increased market concentration and markups in several industries (Leigh 2022; Treasury 2023). Other countries find themselves at similar crossroads and many are – like us – reviewing their competition policy settings.

The Competition Taskforce – supported by an expert advisory panel – has a brief to look at whether Australia’s competition laws, policies and institutions remain fit for purpose.

The Competition Taskforce isn’t just staffed with great people; they’re taking a fresh approach to competition policy: analysing large datasets to understand the challenges and craft solutions. The Taskforce’s data strategy will be a game changer in helping us understand Australia’s competition landscape now and into the future.

Rather than a doorstopper report, the Taskforce will provide the government with continuous advice on competition issues, including a series of short research papers drawing on microdata.

Today, I’m pleased to outline the Taskforce’s research program, which has the ultimate purpose of supporting competition reforms. As part of this, I will preview findings from a few key projects including a newly developed tool that tracks merger activity and an investigation of the impact of competition in the aviation sector in recent decades.

It is notable that these projects all exploit large micro datasets that have only just become accessible in recent years.

A sharper picture: using data to inform competition reform

As numerate as Ben Chifley and the Treasury of the 1940s were, they would have never imagined our capacity to generate, synthesise and analyse data.

Economic dynamism will always be a difficult concept to neatly bundle up and measure as there are so many variables, but microdata can provide new insights.

Microdata includes survey data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics as well as de‑identified administrative data sourced from government agencies such as the Australian Taxation Office and IP Australia.

Like tiny pixels on a giant screen, microdata provides a shaper picture of the competition landscape. This higher definition view can help us understand our weaknesses and deficiencies. And it can help us make the most of opportunities too.

Robust evidence provides transparency and democratic accountability. It tells us where existing policies are working, and where they are not. It has the potential to suggest ways that alternative approaches might better deliver for the Australian public.

Given this, the Competition Taskforce’s data strategy is based on three pillars:

- Building an evidence base to inform immediate competition policy reforms.

- Investing in new data assets to support competition policy development and regulation into the future.

- Embedding the policy and analytical skills within the Australian Public Service and research partners so we can keep creating the evidence that we need for change in the years to come.

The Taskforce’s data strategy is being undertaken in collaboration with other agencies such as the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission as well as think tanks and university researchers.

New research tracking merger activity in Australia

An early achievement of the Competition Taskforce is the development of Australia’s first whole‑of‑economy approach to tracking mergers and acquisitions (Competition Taskforce 2024).

In simple terms, this new approach exploits Australian Bureau of Statistics administrative microdata on labour flows between Australian businesses, adapting a US methodology to identify when a merger takes places. Using labour flows allows the authors to define mergers in an economically meaningful way, excluding mergers that are just trivial paper shuffles.

This research is a collaboration between the Taskforce and researchers from the Reserve Bank of Australia (Jonathan Hambur) and the Australian National University (David Hansell and Nu Nu Win).

The dataset they use comprises the universe of Australian business linked with their employees, and spans 2002–03 to 2017–18.

Using this de‑identified information on businesses, it provides an indication of how many mergers take place each year, and the characteristics of the businesses involved in the merger.

This new approach will create a platform that will enable examination of the impacts of mergers on key economic outcomes, including business performance, employment and industry concentration.

In time, it should also shed light on a range of specific competition issues, for example, the extent and effects of ‘serial acquisitions’ and whether such transactions have been silently contributing to higher market concentration in various industries.

There are three significant findings in these initial results.

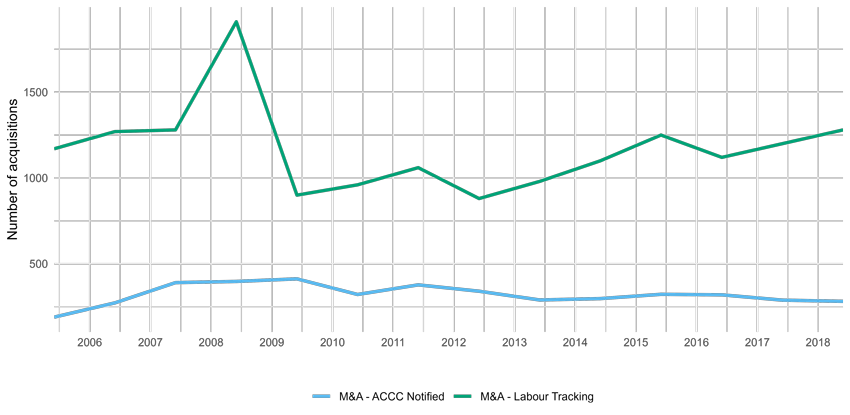

First, the database shows that regulators and researchers currently have only partial visibility of merger and acquisition activity in Australia.

Under the voluntary notification system, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has considered about 330 mergers each year on average over the past decade.

Initial results from the mergers database tracking labour flows suggests there are many more mergers than this each year, somewhere between 1,000 and 1,500. Figure 1 shows the comparison over the period 2004–05 to 2017–18. (Note that the 2008 spike reflects a temporary increase in merger activity in the healthcare sector.)

For every merger that is notified to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, there are two to three more mergers and acquisitions that take place.

Source: ACCC merger statistics; BLADE calculations by Competition Taskforce (2024).

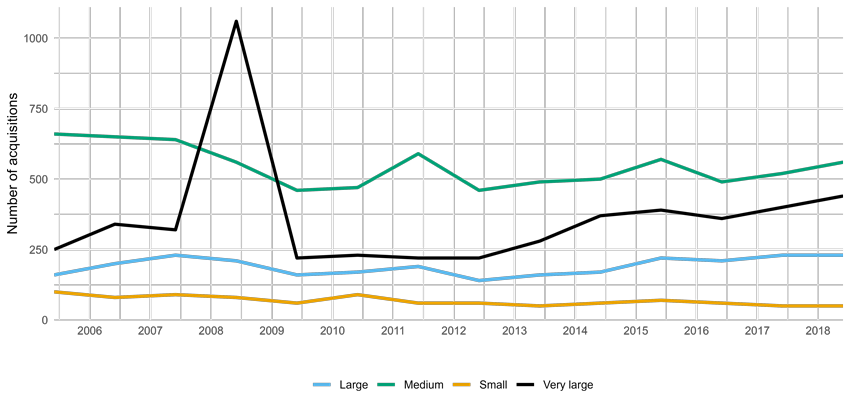

Second, the database reveals acquisitions are disproportionately made by huge firms. The largest 1 per cent of firms make around half of all acquisitions.

The data also shows that larger firms have increased merger activity over the 2010s and that acquisitions are most common in manufacturing, retail, professional services, and health and social services.

Source: BLADE calculations by Competition Taskforce (2024). Small is 1-19 employees, medium is 20-199 employees, large is 200-499 employees and very large is 500 or more employees.

Third, the database shows target merger firms are more likely to have a trademark or patent compared to an average firm. Merger target firms are more than twice as likely to have a patent (0.4 per cent relative to 0.15 per cent of firms overall) and almost twice as likely to have a trademark (4.5 per cent relative to 2.4 per cent of all firms).

This highlights the purchase of intellectual property as a possible motivating factor behind mergers.

While further insights will come to light as additional data sources are added to the database, it already gives us a much more detailed picture of merger activity in Australia than we’ve had before.

As I said earlier, I expect the database will allow Treasury and the research community to dig deeper and examine the impact of mergers on wages, productivity and market share. So the Competition Taskforce’s research is a significant development in terms of harnessing data to put mergers under the competition microscope.

A summary note outlining the methodology and main results is available on the Competition Taskforce’s website, and more detailed results will be released later in the year.

Competition with wings

As the government’s Aviation Green Paper makes clear, a high‑performing aviation sector is critical to Australia’s way of life, connecting people and communities, while supporting economic activity and employment across regions.

Australia accounts for around 1.7 cent of global economic activity (World Bank 2024). Given this, we benefit greatly from adopting and modifying innovation from overseas (Majeed and Breunig 2023; Productivity Commission 2023). Swiftly bringing new ideas and products into our economy has been a major driver of economic growth for decades – and will continue to be so into the future. Travel is an important mechanism for sharing ideas, even in a post‑pandemic world.

A healthy aviation sector means we can be better connected to the rest of the world, better equipped to adopt innovations and better able to help diffuse new ideas within Australia. In short, the aviation sector has large spillovers to other sectors, not just in obvious areas like tourism but right across the economy.

The Competition Taskforce has teamed up with Professor Robert Breunig at the Australian National University for this project.

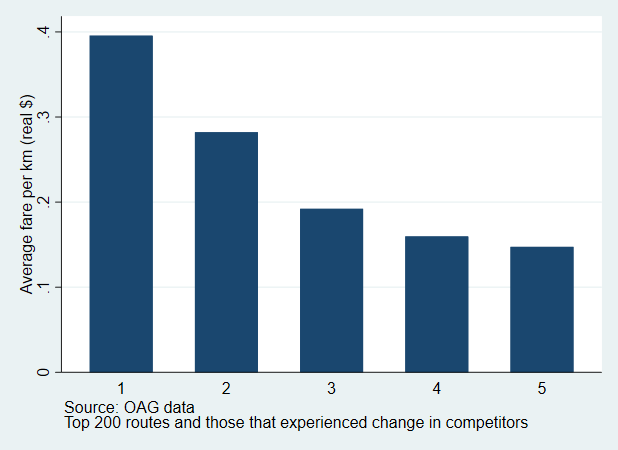

Using detailed microdata from the private sector and the Bureau of Infrastructure and Transport Research Economics, the Taskforce has examined how competition has changed over time and the impact on aviation activity and prices. In an Australian context, it adds to the relatively limited evidence base demonstrating the relationship between competitive pressures and consumer prices.

In particular, initial work by Omer Majeed and coauthors shows how competition has had a significant downward impact on fares. Figure 3 shows how adding airlines to a route reduces fares charged per kilometre by airlines (all figures are in real terms).

When one airline services a route, airfares average 39.6 cents per kilometre. With two competing airlines, the average fare drops to 28.2 cents. With three competitors, to 19.2 cents. In other words, the price per kilometre is halved when three competitors fly a route compared with the situation when there is only a single monopoly airline. With four or five competitors, the price drops further still. (They find these results for all routes and the top 200 routes by passenger traffic.)

Source: Majeed et al 2024 – forthcoming.

Initial results further indicate that the mere threat of competition in the aviation sector has, on average, helped to lower prices.

The team is further developing this analysis, which will support the Taskforce’s contribution to the government’s Aviation White Paper, which is expected to be released in mid‑2024.

Australia’s aviation history shows the value of competition. Prior to the Second World War, more than a dozen airlines operated in Australia, and Australia’s aviation volume was among the highest in the world. But from the 1950s to the 1980s, a duopoly prevailed, keeping prices high. Only with the deregulation of aviation in the late‑1980s did flying become affordable for many middle‑class families and small businesspeople.

Aviation competition has been fundamental to connecting Australian cities to one another, and connecting our country to the world. Still, many Australians suffer from a lack of competition. For example, for a resident of Darwin, it is often cheaper to fly from Darwin to Singapore than it is to fly from Darwin to Sydney – even although the international flight is longer than the domestic one.

Non‑compete clauses

The Competition Taskforce is also investigating non‑compete clauses and other post‑employment restraints.

We have been following the growing body of international evidence around the increasing prevalence of these clauses, and the dampening impact they have on labour mobility and wages growth. Relative to the United States and United Kingdom, Australia is at an early stage in investigating the clauses – but what we know is worrying for competition.

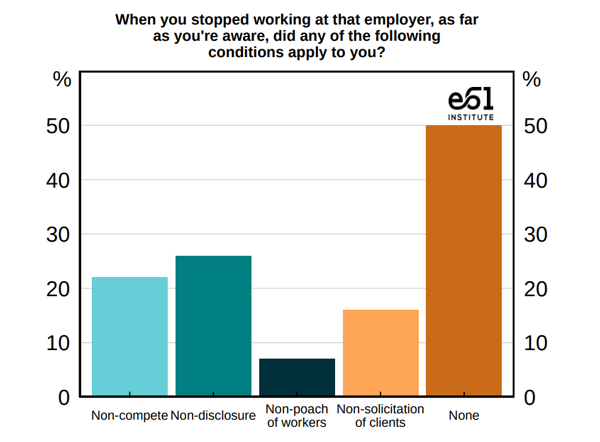

An online survey conducted by Dan Andrews from the e61 Institute and Bjorn Jarvis from the Australian Bureau of Statistics found that one in five Australian workers is subject to non‑compete clauses (Andrews & Jarvis 2023).

Source: e61 analysis of McKinnon Poll conducted by JWS Research.

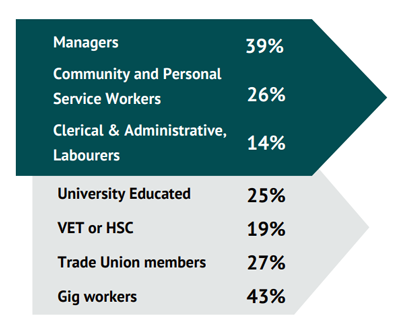

As well as senior executives, Andrews and Jarvis found non‑compete clauses apply to many customer‑facing roles, including childcare workers, yoga instructors and IVF specialists. Figure 5 shows the prevalence of non‑compete clauses across different groups of employees.

Source: e61 analysis of McKinnon Poll conducted by JWS Research.

Shifting jobs is typically associated with a substantial jump in pay. Yet many low‑paid workers are constrained from shifting to a better job. Moreover, even if some non‑compete clauses would not stand up in court, they are rarely tested. In most cases, workers subject to a non‑compete clause will either choose to suffer the period of enforced ‘gardening leave’, or will stay with their existing employer.

This means that workers miss out on potential wage gains. It also makes it harder for start‑up firms to attract the talent they need to challenge incumbents. In turn, productivity suffers.

Soon, the Competition Taskforce and other researchers will be able to draw on data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ inaugural Employee, Earnings and Hours Survey Module on non‑compete clauses, scheduled for release on 21 February 2024.

Analysis of this data will form an important part of the Taskforce’s research and will tell us more about the impact of non‑compete clauses on workers and businesses in Australia.

Future analysis: competition, dynamism and innovation

As part of its data strategy, the Taskforce has several other shorter research papers scheduled for publication this year.

This includes a paper on trends in competition and dynamism.

The idea is to paint a landscape picture of how competition has evolved in Australia and identify any industries that have particularly performed badly.

The updated metrics will include:

- the entry and exit rates of employing businesses

- the job reallocation rate

- industry concentration measures

- the share of high‑growth firms

- markups, and

- the proportion of employment generated by young business.

Initial work confirms that Australian business dynamism has fallen since the early 2000s.

In particular, entry and exit rates of employers, job reallocation, proportion of high growth firms, and proportion of employment by young firms all declined over this period. This experience is similar to other OECD economies.

The Competition Taskforce is also examining how competition can impact on innovation. This work will use microdata and the Business Characteristics Survey of the Australian Bureau of Statistics. It is important analysis because the relationship between competition and innovation is less well understood, especially for Australia (Majeed and Breunig 2023).

Merger reform

I mentioned mergers earlier and you can expect to hear more about how they are regulated in the year ahead.

Mergers aren’t necessarily a bad thing. They can enhance competition if efficiencies are passed on to consumers (Treasury 2023). They can be a healthy way for firms to achieve economies of scale and diversify risk. And they present an efficient way for businesses to exit the market or for their owners to move onto other ventures.

But the small number of proposed mergers that raise competition concerns warrant close scrutiny. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission weighs up a range of factors when assessing whether a merger is likely to be anti‑competitive. This includes:

- market concentration

- barriers to entry

- regulatory or intellectual property constraints

- import competition, and

- product differentiation (ACCC 2008).

It then must assess the likely impact on competition based on the information provided by the merger parties – which is sometimes incomplete and not always provided in a timely way.

These assessments can have a profound impact on the economy. For business, a less competitive market can increase the cost of doing business, and reduce the incentives and opportunities to invest, grow and innovate. For consumers, a less competitive market leads to higher prices, less choice, and lower wage growth.

Therefore, it’s crucial our merger laws, processes and regulations are effective.

The Competition Taskforce issued a consultation paper in November asking whether our current merger regime remains fit for purpose. The Taskforce invited comment on scope for potential changes around:

- the merger notification process

- the test for whether a merger is likely to substantially lessen competition, and

- who should be the ultimate arbiter about whether a merger should proceed.

The paper also canvassed the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s proposed reforms and looked at examples of merger regimes from other jurisdictions.

The Taskforce also invited comment on whether certain types of acquisitions by larger firms are adequately captured by competition laws. This includes creeping or serial acquisitions as I alluded to above – that is a series of smaller acquisitions by large firms which are unlikely to raise alarm bells on their own.

There are also so‑called killer acquisitions – where a large player, such as a pharmaceutical company, snaps up a smaller competitor with the aim of killing off its products or innovations. The paper also highlights concerns about digital platforms using acquisitions to expand their reach into related markets.

The academic literature highlights a curious fact about mergers. According to work by Geoff and J. Gay Meeks, only one in five research papers find that the typical merger boosts profits or sharemarket value (Meeks and Meeks 2022).

In a book titled The Merger Mystery: Why Spend Ever More on Mergers When So Many Fail?, they point out that mergers often boost the remuneration of managers, while leading to layoffs among workers. For the sake of shareholders, workers and citizens, it is important to ensure that Australia’s regulatory system is not facilitating value‑destroying mergers.

The Taskforce has held a large number of stakeholder meetings and received many submissions, receiving a broad range of views on whether our merger rules and processes are working effectively and where they can be improved. Ultimately, as the Treasurer said, any changes to merger settings should deliver benefits to the economy and to consumers while providing certainty to business (Chalmers 2023).

Closing remarks

Australia needs greater competition because it encourages innovation and productivity gains that can be passed on to consumers through lower prices.

Competition helps provide a greater choice of higher quality products.

Competition helps remove inefficiencies in the economy.

Competition helps workers win higher wages.

Like other countries, we’re at a crossroad. There are signs the intensity of competition has weakened across many parts of the economy. The Competition Taskforce analysis of microdata gives us a sharper picture on what’s happening in areas such as mergers and aviation.

The Taskforce will also give us a set of metrics to measure our competition performance and see how we stack up against other countries. Best of all, the Taskforce’s three‑pillar approach to data complements its other activities.

In the year ahead, the Competition Taskforce will:

- provide advice to the government on possible merger reforms;

- provide input into the Aviation White Paper process on ways to increase competition in our aviation sector; and

- release an issues paper and publicly consult on the use and impact of non‑compete clauses in Australia.

The government looks forward to receiving the Taskforce’s advice and research in each of these areas. We recognise that competition isn’t purely a national issue – rather it’s a compact between states, territories and the Australian Government.

And in December last year, the Albanese Government secured agreement from state and territory treasurers to revitalise National Competition Policy and commit to developing an agenda for pro‑competitive reforms.

This will build on the actions we have already taken since taking office in 2022.

We have increased penalties available under the Competition and Consumer Act, strengthened unfair contract term laws, and initiated a review of the Franchising Code of Conduct. We have tasked competition minister Craig Emerson to review the Food and Grocery Code of Conduct, ensuring suppliers get a fair deal.

We have initiated a review by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission into the competitiveness of retail prices and allegations of price gouging in the supermarket sector – the first review such review in 16 years. To help shoppers find the best deal, the Australian Government will fund respected consumer group CHOICE to provide quarterly price transparency and comparison reports – showing which retailers are charging the most and the least.

We are moving ahead with legislation to provide designated consumer and small business advocates with a process where they can report significant or systemic issues to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

And we have committed to addressing unfair practices and agreed to stronger measures to protect consumers and businesses from harms on digital platforms.

Just as Chifley faced the challenges of his era – establishing Snowy Hydro, setting up the Australian National University and creating the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme – we too are focused on the economic priorities of our age. Productivity growth and living standards rely on competition, which is why it is central to our economic agenda for building a stronger economy and a fairer society.

References

Andrews D & Jarvis B 2023 The ghosts of employers’ past: How prevalent are non‑compete clauses in Australia? e61 Institute.

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) 2008 Merger Guidelines.

Beazley, K 2000, 'In the long run', unpublished typescript cited in Hawkins J 2011 Ben Chifley: The True Believer Treasury Economic Round Up Issue 3, Treasury.

Bowen C 2015 The Money Men: Australia’s Twelve Most Notable Treasurers Melbourne University Publishing.

Bowen C 2019 Ambition and Aspiration: Chifley and modern Labor, Inaugural Chifley Lecture, delivered 13 March 2019, Chifley Research Centre.

Chalmers J 20 November 2023 Nation's productivity demands fairness in merger process The Australian [Opinion Piece] published on Treasurer’s website.

Chifley Research Centre 2020 The Light on The Hill, Ben Chifley Speech to the NSW Labor Party Conference, 12 June 1949, Chifley Research Centre.

Competition Taskforce (2024 forthcoming) Tracking mergers in Australia using worker flows, Treasury.

Day D 2007 Ben Chifley in The Oxford Companion to Australian Politics, Edited by Galligan B & Roberts W, page 96.

Holt, E 1969, Politics is People: The Men of the Menzies Era, Angus & Robertson, Sydney cited in Hawkins J 2011 Ben Chifley: The True Believer Treasury Economic Round Up Issue 3, Treasury.

Kennelly P 1963, ‘The Australian Press in a Changing World’, Chifley Memorial Lecture, University of Melbourne, September.

Leigh A 2022 A More Dynamic Economy The Australian Economic Review, 55: 431–440.

Majeed O and Breunig R 2023 Determinants of innovation novelty: evidence from Australian administrative data. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 32(8), 1249–1273.

Meeks G and Meeks JG 2022 The Merger Mystery: Why Spend Ever More on Mergers When So Many Fail? Open Book Publishers.

Productivity Commission 2023 Productivity Inquiry Final Report, Productivity Commission.

Treasury 2023 Merger Reform Consultation Paper Issued November 2023, Treasury Competition Review.

World Bank 2024 World Development Indicators Washington DC.

Text descriptions

Text description of Figure 1: notified mergers vs true merger and acquisition activity

Figure 1 shows two time series lines over the period 2004-05 to 2018-19. The green line shows the number of mergers and acquisitions identified using employee tracking between firms. The blue line shows the number of mergers and acquisitions notified to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. The green line is higher than the blue line by around 1,000.

Text description of Figure 2: number of acquisitions by acquirer size

Figure 2 shows the number of acquisitions by the size of the acquiring firm. There are four categories: small (yellow line: 1 to 19 employees), medium (green line: 20 to 199 employees), large (blue line: 200 to 499 employees) and very large (black line: 500 or more employees). Most of the time, the green line is highest, followed by the black, blue and yellow lines.

Text description of Figure 3: more carriers, lower airfares

Figure 3 shows the average fare per kilometre in 2023 dollars. Each category on the x axis is the number of operators on each route. The highest fare per kilometre is when only one airline flies on the route. Followed by two airlines, then three, four and five. The exact figures are in the speech.

Text description of Figure 4: prevalence of non‑competes and similar restrictions

Figure 4 shows the prevalence of non-compete and other restrictive clauses. It shows the responses to the question ‘When you stopped working at that employer, as far as you’re aware, did any of the following conditions apply to you?’ The five categories are: non-competes (aqua), non-disclosure (green), non-poach of workers (dark green), non-solicitation of clients (peach) and none (orange). It shows about 20% of workers have a non-compete clause and around 25% have a non-disclosure clause. Overall 50% of workers have some form of restriction in their employment contract.

Text description of Figure 5: prevalence of non‑compete clauses across different groups of employees

- Managers: 39%

- Community and Personal Service Workers: 26%

- Clerical & Administrative, Labourers: 14%

- University Educated: 25%

- VET or HSC: 19%

- Trade Union members: 27%

- Gig workers: 43%