I acknowledge the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung and Bunurong Boon Wurrung peoples of the Eastern Kulin.

I pay my respects to their Elders, extend that respect to other First Nations people present, and commit myself, as a part of the Albanese Government, to the implementation in full of the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

Special thanks to Per Capita and Maurice Blackburn for hosting today’s event.

Company Towns

Sixteen Tons was written by Merle Travis in 1946.

It’s been covered many times, most famously by Johnny Cash.

It’s about a real group of coal miners who lived and worked in a company town in Muhlenberg County, Kentucky. The chorus goes:

You load 16 tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt

St. Peter, don't you call me 'cause I can't go

I owe my soul to the company store (Travis 1946)

To Merle Travis, those words were personal. The first two lines came from his brother. The last two lines came from his father. Both had experienced what it felt like to work all day and get paid not in cash, but in scrip – redeemable only at the company store.

Folk music fans might also be familiar with Pete Seeger’s ‘Homestead Strike Song’ (Seegar 1980), written about another company town.

Homestead, Pennsylvania was a company town built in the 1880s to supply workers to Andrew Carnegie’s steel mills.

The men worked in the foundries and raised their families in the purpose-built town.

They made railway lines and bridges and steel for the Empire State building (Russell 1992).

A contract between the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers union and Carnegie Steel was due to expire on 1 July 1892.

Carnegie gave his operations manager permission to break the union before the contract ended.

Wages were cut and workers locked out of the plant. They went on strike and all 3,800 were fired the following day.

On 6 July 1892, the steel workers fought for control of the factory and the town against strike breakers shipped in under cover of night by Carnegie’s managers.

In a 12-hour gun battle and its aftermath three strike breakers and seven workers died.

Ultimately, the strike failed, and the plant was operational again within days.

Another company town that inspired ballads was Pullman, Illinois.

It was developed outside Chicago in the 1880s by George Pullman who made his fortune building train carriages, specialising in luxury sleeper cars.

The Pullman strike is considered one of the great turning points in U.S. industrial history.

Pullman built his model town to house workers for his train carriage manufacturing business.

He owned it all: the houses, the market, library, church, and schools.

The town was home to 6,000 employees and their families who rented from the Pullman company.

But demand for Pullman cars tanked during a depression that followed the economic panic of 1893.

The company laid off hundreds of workers and switched many more to pay-per-piece work.

But the rents didn’t go down.

Discontent had been brewing in Pullman. There was resentment over the boss’s paternalistic control of workers’ lives, the prices charged for services, high rents and because they weren’t allowed to own their own houses. (Almont, 1942).

First came a strike by the American Railway Union in spring 1894.

When that failed, the union launched a national boycott of trains pulling Pullman carriages.

The boycott lasted two months and ended only after the federal government and military intervened.

A national strike commission that later investigated the causes of the strikes and found Pullman Company partly to blame, labelling its actions ‘Un-American’ (Buder, 1967).

Pullman was meant to be the model town watched over by a benevolent boss.

But in 1898 the Pullman Company was ordered to divest ownership of the town and it was annexed to Chicago.

Company towns peaked around the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Boyd 2003).

Pullman was probably the most spectacular failure, certainly in the U.S.

But it seems such utopian dreams linger, even today.

In March 2021, Elon Musk announced plans to incorporate the site of a SpaceX rocket manufacturing and launch facility, with a city called Starbase. Presumably it’s a trial run for SpaceX company towns on Mars.

The story of the company town in Australia is a bit different.

Here they were usually established to accommodate workforces in remote places.

Roxby Downs in South Australia was built for development of the Olympic Dam mine.

Mount Beauty and Bogong Village in north east Victoria were built by the State Electricity Commission for Kiewa Hydroelectric Scheme construction workers.

Useless Loop on the West Australian coast is a closed company town owned by Japan’s Mitsui Group. And in case you’re wondering, the town’s name came from a French explorer who disliked the harbour (Bilson 2015), not from an economist analysing the way that money typically flows around a company town.

And then there are the Australian company towns that operate with a fly-in, fly-out workforce, such as Newman and Barrow Island.

While company towns have declined in advanced economies, concerns about employer market power have been gaining traction in recent years.

Some see wannabe ‘modern company towns’ in situations where a single employer dominates a large portion of a local labour force (Willingham and Aijilore 2019).

This is where monopoly and monopsony meet.

The Origins of Monopsony

The trailblazing Cambridge University economist Joan Robinson – who should have been the first woman to win the economics Nobel Prize – is credited with popularising the term monopsony.

Building on Adam Smith’s concerns over monopoly, Robinson challenged accepted wisdom in her male-dominated profession by rejecting the idea of perfect markets.

This meant contradicting the formidable Alfred Marshall, who had long dominated economics at Cambridge.

He argued that supply and demand could meet in perfect equilibrium when workers were paid precisely the value of their contribution to production.

This, Marshall said, gave consumers the upper hand because companies had to compete on price and quality in a competitive market.

The problem was Marshall’s conviction that monopoly was a passing flaw that would correct itself over time.

Robinson disagreed (Carter 2021).

In 1933, at the age of thirty, Robinson published her landmark book The Economics of Imperfect Competition (Robinson 1933).

Monopoly, she argued, didn’t have an on-off switch.

And truly competitive markets were rare.

In a monopoly the consumer pays the price set by the supplier.

In a monopsony the supplier accepts the price set by the buyer.

Monopolies hurt consumers.

Monopsonies hurt suppliers.

In the labour market, workers are suppliers.

The service they supply is their labour.

As citizens we don’t typically think of ourselves as suppliers, but in the labour market, that’s precisely what we are.

Robinson argued that monopsony was endemic in the labour market and employers were using it to keep wages low.

If there are a small number of employers competing for workers, those workers have fewer outside options. Their bargaining power is limited.

Therefore, employers have the power to set lower wages.

In the extreme case, think of the plight of employees in Muhlenberg, Homestead, Pullman and those other one-company towns.

Workers benefit when there are more employers in the labour market. More employment options mean greater bargaining power.

Workers can swap jobs and move on to better pay and conditions with another employer.

I will discuss a little later just how important this is in the Australian context.

Monopsony Roars Back

Joan Robinson died in 1983, and monopsony fell out of favour among many economists in the ensuing decades. But in recent years, Robinson and monopsony have made a return to the economic big time.

Last year, the Journal of Human Resources released a special issue focused on monopsony in the labour market.

It was an acknowledgement of the growing focus of market power in economic literature (Ashenfelter et al 2022).

As the editors of the special issue argued:

‘The idea that firms have some market power in wage-setting has been slow to gain acceptance in economics.

‘Indeed, until relatively recently, the textbooks viewed monopsony power as either a theoretical curiosum, or a concept limited to a handful of company towns in the past.

‘This view has been changing rapidly, driven by a combination of theoretical innovations, empirical findings, dramatic legal cases, and new data sets that make it possible to measure the degree of market power in different ways.’ (Ashenfelter et al 2022)

The concept has also caught the attention of competition lawyers. Monopsony was cited in a ruling against Apple in the US Supreme Court in 2019.

The Court found:

‘A retailer who is both a monopolist and a monopsonist may be liable to different classes of plaintiffs — both to downstream consumers and to upstream suppliers — when the retailer’s unlawful conduct affects both the downstream and upstream markets.’ (Supreme Court 2019)

Think of iPhone users as consumers in a monopoly market. They are likely to pay more for a product because of the seller’s market dominance. When the iPhone 15 hits the shelves in September, there’s only one company that will sell it to you.

But you can also think of Apple’s app developers as suppliers in a monopsony. They are likely to get less for the product they are selling because Apple has the monopsony on which apps run on its systems. There’s a reason that Apple can take a cut of 30 per cent on most in-app purchases: because there’s only one way of getting an app onto an Apple phone.

Both consumers and suppliers lose.

Monopoly meets monopsony.

A report by US House Democrats accused Amazon of using monopsony power in its warehouses to ‘depress wages’ in local markets (Nadler and Cicilline 2020, 303-304).

They described Amazon as acting like a monopsony because of the way it pressured third-party suppliers to lower their prices if they wanted to sell products through the behemoth’s platform.

These were the characteristics of a monopsony, according to the Democrats, because of Amazon’s market dominance, interactions with suppliers and behaviour in the labour market.

Perhaps this is a case of the company town gone global.

International Evidence on Employer Power

Evidence from the US, UK and Europe has demonstrated that increases in labour market concentration are associated with lower wages (Benmelech, Bergman and Kim 2022; Azar, Marinescu and Steinbaum 2022; Abel, Tenreyro and Thwaites 2018; Jarosch, Nimczik and Sorkin 2019).

Without market power, economic theory would predict that wages are equal to a worker’s marginal product of labour – the increase in output as additional labour is used.

With market power, an employer can set lower wages, meaning a worker is producing at a higher level than they are being paid.

Studies of the US and Europe find that the impact is larger in rural labour markets, potentially reflecting fewer opportunities and larger employer power outside metropolitan areas.

Economists have long noted that people in cities tend to earn more than those in regional areas. My own research finds that when someone moves from a rural area to a major Australian city, their annual income rises by 8 per cent (Leigh 2014, 84-85).

The economics of monopsony suggests that an important part of the urban wage premium can be explained by greater employer competition in denser labour markets (Hirsch et al 2022).

A recent US paper found that workers may produce 21 per cent more than they earn, suggesting significant monopsony power (Azar, Berry and Marinescu 2022).

In other words, for every $1.21 of value that employees produce, they are paid $1 in wages.

While the level of employer concentration appears to be fairly stable over time in the US, the negative relation between concentration and wages has been increasing in magnitude over time (Benmelech, Bergman and Kim 2022).

In areas with few employers, those firms are increasingly wielding their power to suppress wages.

Australian Evidence on Employer Power

In Australia, as in many other nations, wage growth has been slow.

The average weekly full-time wage in November 2022 was $1,808 a week.

In 2022 dollars, the average wage in November 2012 was $1,790 a week.

In other words, after inflation, Australian workers earned only $18 per week more in November 2022 than they did in November 2012.

Fundamental determinants such as productivity and inflation expectations have played a role, but even so growth has still been lower than expected (Andrews et al. 2019).

At the same time, the rate at which people move between employers has also fallen.

Forget what you’ve heard about the joys of a ‘job for life’.

Across a career, the biggest average wage gains come when people switch employers.

For a worker who is keen for a pay rise, the best chance is to get a new job – or at least a new job offer (Deutscher 2019).

And by the way, people who switch roles won’t be hurting their co-workers.

When some employees switch jobs, it also tends to mean better wages for stayers, as they can leverage the option to switch when negotiating with their employers.

Why have job switching rates fallen? And why has wage growth been so slow?

Increases in employer concentration, and larger impacts of employer concentration on wages could explain both phenomena.

A newly released Treasury working paper by Jonathan Hambur considers whether labour market concentration lowered wages growth pre-COVID.

The paper explores the trends in and impacts of monopsony power in Australia (Hambur 2023).

Defining a labour market as the intersection of a region, and an industry, it uses rich de-identified tax data to measure concentration in labour markets across the country.

The analysis separates Australia into 290 working zones (for example Canberra, Kalgoorlie, and Townsville) and 190 industries (for example coal mining, residential building construction, and life insurance).

For example, it might look at the concentration of employers for grocery stores in Wagga Wagga.

Altogether, the analysis separates Australia into around 25,000 local labour markets per year.

Employment concentration is measured using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). This ranges from zero for a perfectly competitive market to one for a monopsony employer (such as in a one-company town).

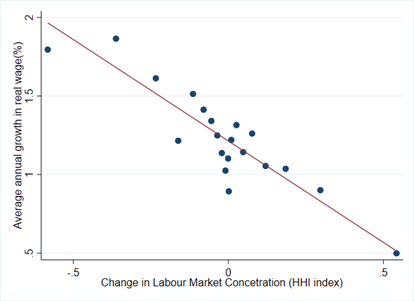

Hambur’s research reveals that in Australia, wages tend to be lower in more concentrated markets.

Within markets where concentration rose, real wage growth over the decade was significantly lower (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Employment Market Concentration and Wage Growth, change from 2005 to 2016

Source: Hambur (2023)

On average, larger firms are more productive. The turnover per employee is likely to be lower at a corner store than at a big supermarket.

Thanks to more capital, more efficient management systems, and the benefits of scale, larger firms tend to be more productive, and tend to pay higher wages.

But when a labour market is more concentrated – or when a firm has a larger share of the employment market – the gap between the value a worker produces, and the wage they are paid, tends to grow.

This means larger firms set lower wages once other factors – such as productivity – are taken into account.

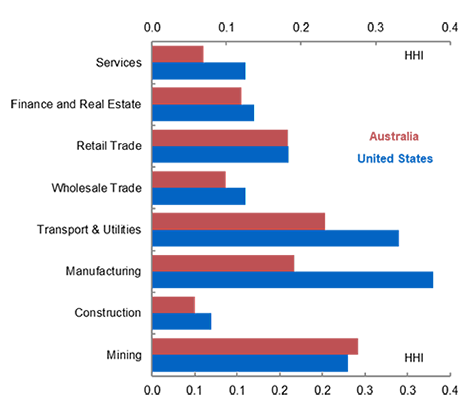

While the level of concentration in Australia is lower than in the US, there is substantial variation across labour markets.

Figure 2 shows that pattern of market concentration across industries and compares the results with those in the United States.

Employer concentration in the Australian labour market is highest in the mining industry, manufacturing, transport, utilities and retail trade.

For most industries, concentration is higher in the United States. But in the case of mining, employment concentration is slightly higher in Australia.

Figure 2: Employment‑weighted Average HHI by Sector, 2012

Notes: Services include Accommodation and Hospitality, Information, Media and Technology, Professional Services, Administrative Services, Arts & Recreation, and Other Services. Interpretation of the results for mining might be affected by fly‑in‑fly‑out work. Figure shows HHI measures in 2012 given data availability of the US comparison.

Source: Hambur (2023); Rinz (2018)

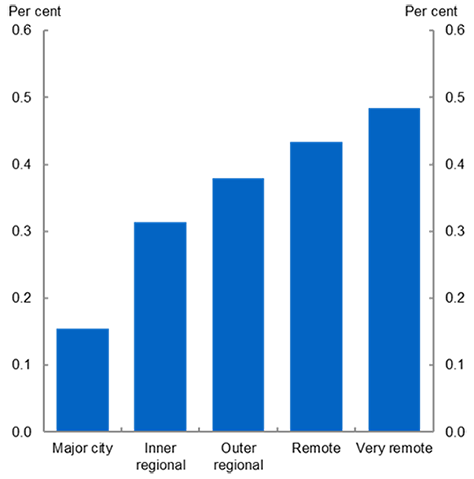

Figure 3 looks across regions in Australia, estimating the average level of employer concentration in cities, regional areas and remote Australia.

It shows that employment is twice as concentrated in inner regional areas as it is in major cities.

In remote areas, employment concentration is three times as high as in major cities.

This suggests that monopsony power may be a particular problem for those living outside major cities.

Figure 3: Unweighted Average Employment HHI for 2005‑2016, by Remoteness

Notes: Remoteness based on ABS remoteness structures.

Source: Hambur (2023)

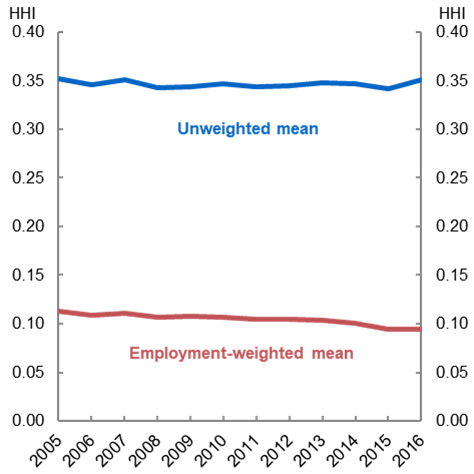

The Treasury analysis shows that while labour markets in Australia have not become more concentrated over time (Figure 4), the negative impact of any given level of concentration on wages has increased.

For any given level of concentration, its negative impact on wages has more than doubled compared to the mid-2000s.

Because of this – and despite no increase in concentration – employer market power could be a factor that has influenced the slow growth of wages over the last decade.

The greater impact of concentration may have lowered wages by around 1 per cent from 2011 to 2015 (Hambur 2023).

This could help explain why the share of productivity gains passed through to workers has declined modestly over the past 15 years (Andrews et al. 2019; e61 Institute 2022).

Figure 4: Average Employment HHI over time

Source: Hambur (2023)

The Treasury analysis finds that declining firm entry and declining economic dynamism appear to be important factors contributing to the increased impact of concentration.

When firms enter, they tend to compete and poach staff away from existing firms to grow.

As such, they create better outside options for workers.

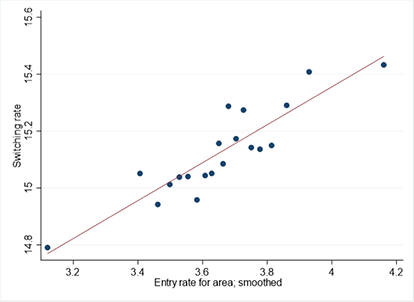

When entry rates are high, people are more likely to switch jobs, and this relationship is driven by people moving from incumbent to young firms (Figure 5).

So, when entry rates are higher, even if markets are still somewhat concentrated, there are more outside options for workers, lessening the effects of concentration on wages.

Figure 5: Entry Rate vs Job-to-job Switching by SA4 for 2002-2016

Source: Hambur (2023)

Overall, Hambur (2023) provides new evidence on monopsony power in Australia, adding to the growing literature on dynamism, competition and market power.

We’ve always known that monopolies hurt the average person. By transferring resources from consumers to shareholders, they make the typical family worse off, and worsen inequality (Gans et al 2019).

But now we can see another effect.

If those monopolies also exert monopsony power, then they may drive down wages.

Workers may get a smaller pay packet because of monopsony power, and then find that when they try to spend it, they get less for their money because of monopoly power.

It’s a double squeeze.

Dynamism, Competition and Market Power

Last year, I delivered four major speeches on economic dynamism and competition.

In the Gruen Lecture at the Australian National University, I presented new evidence on the decline in market dynamism.

Thanks to extraordinary new data, we are now able to analyse the economy at a fine-grained level and look at changes over time.

This reveals a troubling picture.

Over recent decades, the new business start-up rate has declined. Market concentration has risen.

The biggest companies on the Australian share market have barely changed in a generation.

In the Warren Hogan Lecture at the University of Sydney, I delved into three moments in history where countries had experienced major boosts in economic productivity as a result of competition reform.

These were the US Sherman Act and Teddy Roosevelt’s vigorous enforcement of competition laws, Germany and the post-war breakup of industrial giant IG Farben, and Canada’s 1985 competition reforms.

At a Sydney Ideas talk marking the 30th anniversary of the Hilmer reforms, I discussed the competition reforms spearheaded by Fred Hilmer and Paul Keating, which led to the removal of anti-competitive regulations, the creation of a national electricity market and the prioritisation of competition across governments.

The changes contributed to the 1990s surge in productivity.

On one estimate, the typical Australian household is $5,000 a year better off as a result.

And at the Sydney Institute, I explored the issue of price markups – noting that the gap between firms’ cost of production and the price they charge has been steadily rising.

It’s a finding that is quite consistent with the growth in market concentration, and highly relevant at a time when inflation is surging around the world.

Bigger markups didn’t cause our inflation problems, but they’re one of the reasons that people are paying more than they should be for everyday necessities.

Alongside this, I’m pleased to see a growing focus among researchers on issues of market dynamism.

Work by the new e61 Institute has highlighted the negative implications of declining dynamism on productivity and, therefore, wages (e61 Institute 2022; Andrews et al 2022).

Monopsony power suggests another mechanism through which declining business dynamism might have lowered wages growth.

The labour market today is less dynamic than in the past.

Treasury estimates that the share of workers starting a new job in the previous three months declined from an average of 8.7 per cent over the period of February 2002 to May 2008 to 7.3 per cent from August 2008 to November 2019.

Monopsony power has weakened workers’ outside options and bargaining power, made labour markets less competitive and, therefore, lowered workers’ wages.

A more dynamic and competitive economy will help improve labour market outcomes.

Tackling Monopsony Power

So, what is to be done?

In the area of monopsony power, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has in the past taken on misconduct by firms with regard to their suppliers.

One such action arose in Victoria in 1994 and 1995. Safeways supermarkets had a policy that when a bread supplier sold bread to independent retailers at a lower price than their stores, Safeway temporarily stopped purchasing from that bread supplier. The competition watchdog was largely successful in court, determining that misuse of market power could apply to suppliers as well as customers – in other words, that competition law applied to monopsonists as well as monopolists (Australian Government Solicitor 2003).

Other actions against anti-competitive conduct by suppliers have involved unfair contract terms. In one case, chicken processors were imposing contracts on their suppliers which allowed them to vary supply agreements or impose additional costs.

In another, potato processors had contracts with farmers that let them unilaterally vary the price and prevent suppliers from selling to other processors.

Wine makers were also found to be abusing their power over grape growers by including provisions that allowed them to unilaterally vary the contract and prevent them seeking legal or financial advice.

Another instance of monopsony power arose from the decision by dairy processors Fonterra and Murray Goulburn to retrospectively cut their suppliers’ prices – a process known as ‘clawback’. This spurred the creation in of the Dairy Code of Conduct, and a class action that was settled last year with Fonterra agreeing to pay suppliers $25 million in compensation.

In a note prepared for the OECD last year, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission concluded ‘our market studies in a range of sectors demonstrate that buyers’ power, and the inequality of bargaining power that underlies it, creates real risks of potential harm to the effective operation of markets’ (ACCC 2022). The Commission pointed to enforcement action under fair trading laws and industry-specific regulation as a check on buyers’ power.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has also considered monopsony power in other contexts. When assessing mergers, it can take account of buyer power – and has done so in relation to proposed mergers between food processors and food suppliers. The Commission recently issued a class exemption for businesses with turnover below $10 million to collectively bargain with suppliers or customers – providing a safe harbour for their dealings with customers who may have monopsony power. The Commission has also used the unfair contract terms provisions in the legislation to obtain an enforceable undertaking from a franchisor that was preventing ex-franchisees from setting up competing businesses. And in its fifth Digital Platform Services Inquiry Report, the Commission proposed new powers that could reign in abuses of monopsony power by technology platforms.

However, Australian competition law specifically carves out matters relating to earnings, hours or conditions of employment (Competition and Consumer Act 2010, s51(2)). So I have been unable to identify instances in which the competition watchdog has taken enforcement action against firms engaged in labour market collusion.

This contrasts with the United States, where Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter recently told a Senate committee hearing:

‘One area where we have been particularly active is prosecution of criminal conspiracies among employers. Labor market competition is essential to a properly functioning market-based economy. Free market competition for workers can mean the difference between saving for a home, sending kids to college, and leaving a toxic workplace, or being forced to stay. It also means free market competition for entrepreneurs, small business owners, and honest businesses of all kinds who compete to attract and retain talented workers…

‘Criminal conspiracies in labor markets include wage fixing and allocation agreements that limit worker mobility or suppress wages. … Outside of the reach of a labor exemption, agreements by employers to restrict labor market competition is entitled to no special treatment under the U.S. antitrust laws. We will continue to prosecute collusion in labor markets that serves no other purpose than to cheat workers of competitive wages, benefits, and other terms of employment.

‘In the last two years, the [Antitrust] Division has brought six criminal cases … labor market collusion is a felony under the Sherman Act. As one court explained: “employees are no less entitled to the protection of the Sherman Act than are consumers” and “anticompetitive practices in the labor market are equally pernicious — and are treated the same — as anticompetitive practices in markets for goods and services”.’ (Kanter 2022)

A particular concern in the labour market is non-compete and no-poach clauses.

On one estimate, 18 per cent of US workers are currently subject to a non-compete clause, and 38 per cent have been subject to one at some point in their career (Starr, Prescott and Bushara 2021).

Non-compete clauses are not restricted to high-wage jobs. In the US, non-compete clauses bind 11 per cent of landscapers, 12 per cent of construction workers, 18 per cent of installers and 19 per cent of personal care workers (Starr 2019). Even in US states where non-compete agreements are unenforceable, many workers end up signing contracts containing such clauses.

No-poach clauses have a similar effect to non-compete clauses, by constraining employers from engaging workers who have recently been employed at a competing outlet. From the 1980s to the 2010s, a group of Silicon Valley companies – including Pixar, Apple, Google, Adobe and Intel – colluded in an agreement to not attempt to hire each other’s technology workers (Ashenfelter et al 2022). Only a lawsuit from the Department of Justice finally ended the conspiracy.

No-poach clauses also turn out to be ubiquitous in franchises. Analysing franchise agreements, researchers found that no-poach clauses existed in 58 per cent of major franchisors’ contracts, including McDonald’s, Burger King, Jiffy Lube, and H & R Block (Krueger and Ashenfelter 2022).

In Australia, I have been unable to find any surveys of the prevalence of non-compete clauses.

On no-poach clauses, the only evidence comes from an exercise that I conducted in 2019, writing to all Australia’s major franchisors to ask whether their standard franchise agreement included a no-poach clause (Leigh 2019).

Among them, McDonald's, Bakers Delight and Domino’s wrote back to me to say that their standard clauses prevent franchisees from hiring workers in other stores. For example, McDonalds told me that each franchised store in Australia must sign a contract that says ‘neither licensee nor principal shall employ or seek to employ any person who is at the time employed by McDonald’s or by licensor or by any of the subsidiaries or associated or related companies of McDonald’s or licensor or by any person who is at the time operating a McDonald’s restaurant, or otherwise induce, or attempt to induce, directly or indirectly, such person to leave such employment’.

Most McDonald's workers would have no idea about this clause, which directly affects their ability to get a better-paying job at another McDonald's store.

To their credit, at least these three retailers replied. Many of the large franchise chains simply ignored the request.

Unlike the US, there is no requirement for their franchise contracts to be publicly lodged, so we can’t know the full extent to which other franchise chains are reducing the competition for workers.

What can policymakers do?

In the US, the Federal Trade Commission has concluded that scrapping non‑compete clauses could boost worker earnings by almost US$300 billion, and close racial and gender pay gaps by up to 9 per cent.

Accordingly, the Federal Trade Commission has now proposed a total ban on non-competes across the US economy (FTC 2023).

Announcing the proposal, Federal Trade Commission chair Lina Khan said:

‘The freedom to change jobs is core to economic liberty and to a competitive, thriving economy. Non-competes block workers from freely switching jobs, depriving them of higher wages and better working conditions, and depriving businesses of a talent pool that they need to build and expand. By ending this practice, the FTC’s proposed rule would promote greater dynamism, innovation, and healthy competition.’

The comment period on the proposed ban runs until 20 March 2023.

In Australia, non-compete clauses are only enforceable if they can be shown to reasonably protect a legitimate business interest.

In judging such cases, courts may consider the duration, geographic area and industry reach of the non-compete clause.

On this basis, some have argued that the deterrent effect of Australian non-compete clauses on worker mobility is limited.

However, this ignores the findings from US research that even in states such as California, where non-compete clauses are unenforceable, they still exert an effect.

There are a number of reasons for this, including workers not being perfectly aware of all their legal rights, and the financial risk to an employee of facing off against their former employer in court.

As one Australian website advises employers, ‘It’s easy to insert [a non-compete clause] into an employment contract’.

Even if it might turn out to be unenforceable, why wouldn’t a rational employer try to block competitors?

Given the growing body of evidence about the way that non-compete clauses hamper job mobility and wage growth, I have asked the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and Treasury for advice on the competitive impacts of non-compete clauses and any action the Australian Government should take in response.

Last year, I introduced into parliament a ban on unfair contract terms, and the bill subsequently passed into law. As the ban only applies to consumer and small business contracts, which do not include employment contracts, this new provision likely does not apply to non-compete clauses.

Nonetheless, you could readily argue that the principle still holds. Why should we ban unfair contract terms when it comes to a big business contracting with a small businesses, yet allow unfair contract terms when it comes to a big business contracting with an individual employee?

As to no-poach clauses in franchise agreements, they could not be struck down as an unfair contract term. That’s because the disadvantage is to the employee, who is not a party to the franchise agreement.

But at a minimum, it would be useful to know more about the prevalence of these clauses.

I encourage Australia’s large franchisors to publicly disclose whether their standard agreements contain no-poach clauses, and, if so, to justify why they are in the public interest.

Unions also have a critical role to play in curbing monopsony power.

In both the US (Benmelech, Bergman and Kim 2022) and Australia (Hambur 2023), the impact of market concentration on wages is smaller when union membership rates are higher.

Yet over recent decades, the share of Australian workers who are union members has steadily declined, dropping from 41 per cent in 1992 to 12.5 per cent in 2022.

Not since 1901 has the Australian unionisation rate been as low as it is today.

Deunionisation is not the primary reason for a decade of wage stagnation. But at a time when the market power of employers is growing, declining union membership risks tilting the playing field further away from workers.

As the chant goes, ‘the workers, united, will never be defeated’.

But in the modern era, employers are increasingly united, while workers are more fragmented than at any time in the past 120 years.

Providing employees with more opportunities to collectively bargain for better pay and conditions would be a useful check on monopsony power.

Conclusion

Two young fish are swimming along one day when they meet an older fish. As they pass, the older fish happily greets them with ‘hey guys, how’s the water?’.

As the older fish swims off, one of the younger fish turns to the other and asks, ‘what the heck is water?’.

To many Australian workers, monopsony is the water we swim in each day.

Yet unless a wise fish like Johnny Cash or Joan Robinson points it out, it’s easy to miss the pernicious impact that monopsony power has on the economy.

In this speech, I have outlined some of the facts about monopsony power in Australia.

Concentrated labour markets are a particular problem in Australian regions.

While labour markets in Australia have not become more concentrated over time, the negative impact of any given level of concentration on wages has increased.

For any given level of concentration, its negative impact on wages has more than doubled compared to the mid-2000s.

On one estimate, the greater impact of concentration may have lowered wages by around 1 per cent from 2011 to 2015.

In turn, this could help explain why the share of productivity gains passed through to workers has declined over the past 15 years.

Monopsony power is also closely connected with firm entry. In areas with fewer new firms, people are less likely to switch jobs. And we know how crucial job-switching is to wage growth.

In the United States, strong enforcement action has seen a number of prosecutions of cartels that were aiming to suppress wages.

That country’s competition regulator has also proposed a nationwide ban on non-compete clauses, arguing that this will boost wages and narrow the gender pay gap.

While the Australian Government has not reached a fixed view on whether new action is needed to tackle the impact of market concentration on wages, we are watching these developments closely and seeking advice from the key economic and competition agencies.

A focus on monopsony has been a long time coming.

It took economists too long to recognise the problems of monopsony power, and the way that monopoly and monopsony can be two sides of the same dodgy coin.

Sometimes those who have championed workers’ rights have been sceptical of competition reforms, seeing them as threatening a race to the bottom on wages.

In fact, as Joan Robinson has shown us, uncompetitive markets don’t just hurt consumers, they can hurt workers too.

It’s another reason we’re working to shape a more dynamic economy, a more productive corporate sector, and a fairer society.

References

Abel, Will, Silvana Tenreyro and Gregory Thwaites (2018), ‘Monopsony in the UK’, Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper DP13265.

Almont, Lindsey. The Pullman strike: the story of a unique experiment and of a great labor upheaval, Chicago, Illinois, The University of Chicago Press, 1942.

Andrews, Dan, Nathan Deutscher, Jonathan Hambur and David Hansell (2019), ‘Wage Growth in Australia: Lessons from Longitudinal Microdata’, Australian Treasury Working Paper, No 2019-04.

Andrews, Dan, Jonathan Hambur, David Hansell and Angus Wheeler (2022), ‘Reaching for the Stars: Australian Firms and the Global Productivity Frontier’, Australian Treasury Working Paper, No 2022-01.

Ashenfelter, Orley, David Card, Henry Farber, Michael R Ransom (2022) ‘Monopsony in the Labor Market: New Empirical Results and New Public Policies’, Journal of Human Resources 57, no. 7, pp S1-S10. muse.jhu.edu/article/850932

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2022) ‘Purchasing Power and Buyers’ Cartels – Note by Australia’, Prepared for the 138th OECD Competition Committee meeting on 22-24 June 2022, OECD, Paris.

Australian Government Solicitor (2003) ‘Misuse of Market Power and Price Fixing’, AGS Casenote. https://www.ags.gov.au/sites/default/files/07AGSCasenoteSafeway.pdf

Azar, Jose, Steven Berry and Ioana Marinescu (2022) 'Estimating Market Power', NBER Working Paper 30365.

Azar, Jose, Ioana Marinescu and Steinbaum (2022) 'Labour Market Concentration', Journal of Human Resources, 57, pp S167-S199.

Benmelech, Efraim, Nittai K. Bergman and Hyunseob Kim (2022), ‘Strong Employers and Weak Employees: How Does Employer Concentration Affect Wages?’, The Journal of Human Resources, 57(S), pp S200–S250.

Bilson, Ross (2015) ‘Useless Loop 6537: Heart of the Nation’, The Weekend Australian Magazine, 7 March 2015. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/weekend-australian-magazine/useless-loop-6537-heart-of-the-nation/news-story/14208f19aa58938dce4caff4eea1cfce

Bishop, James, and Iris Chan (2019), ‘Is Declining Union Membership Contributing to Low Wages Growth?’, Reserve Bank of Australia Research Discussion Paper No 2019-02.

Boyd, Lawrence. The Company Town, EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples, 30 January 2003. http://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-company-town/

Buder, Stanley. Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning, 1880-1930. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/imh/article/view/9315/12544

Carter, Zachary (2021) ‘The woman who shattered the myth of the free market’, New York Times, 24 April 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/24/opinion/joan-robinson-economy-monopoly-labor.html

Deutscher, Nathan (2019), ‘Job-to-Job Transitions and the Wages of Australian Workers’, Australian Treasury Working Paper, No 2019-07.

e61 (2022) ‘Better Harnessing Australia’s Talent: Five Facts for the Summit’, e61 institute.

FTC (2023) ‘FTC Proposes Rule to Ban Noncompete Clauses, Which Hurt Workers and Harm Competition’, Federal Trade Commission. https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/01/ftc-proposes-rule-ban-noncompete-clauses-which-hurt-workers-harm-competition

Gans, Joshua, Andrew Leigh, Martin Schmalz and Adam Triggs (2019) ‘Inequality and market concentration, when shareholding is more skewed than consumption’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 35(3), pp 550-553.

Hambur, Jonathan (2023) ‘Did Labour Market Concentration Lower Wages Growth Pre-COVID?’ Australian Treasury Working Paper.

Hirsch, Boris, Elke Jahn, Alan Manning and Michael Oberfichtner (2022) ‘The Urban Wage Premium in Imperfect Labor Markets’, The Journal of Human Resources, 57(S), pp S111–S136.

Jarosch, Gregor, Jan Nimczik and Isaac Sorkin (2019), ‘Granular Search, Market Structure, and Wages’, NBER Working Paper No 26239.

Kanter, Jonathan (2022) ‘Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter of the Antitrust Division Testifies Before the Senate Judiciary Committee Hearing on Competition Policy, Antitrust and Consumer Rights’, United States Department of Justice. https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-jonathan-kanter-antitrust-division-testifies-senate-judiciary

Krueger, Alan, and Orley Ashenfelter (2022) ‘Theory and Evidence on Employer Collusion in the Franchise Sector’, The Journal of Human Resources, 57, pp S324-S348.

Leigh, Andrew (2014) The Economics of Just About Everything, Allen and Unwin, Sydney.

Leigh, Andrew (2019) ‘Time to axe the cosy deals and fix the labour market’, Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/national/time-to-axe-the-cosy-deals-and-fix-the-labour-market-20191003-p52xb9.html

Leigh, Andrew (2022a) ‘A More Dynamic Economy – Speech’, Fred Gruen Lecture, Australian National University, Canberra, 25 August 2022.

Leigh, Andrew (2022b) ‘A Zippier Economy: Lessons from the 1992 Hilmer Competition Reforms – Speech – Sydney Ideas’, University of Sydney, 17 October 2022.

Nadler, Jerrold and David Cicilline (2020) ‘Investigation of Competition in Digital Markets’, Majority Staff Report and Recommendations: Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law of the Committee on the Judiciary, United States.

Rinz, Kevin (2018), ‘Labor Market Concentration, Earnings Inequality, and Earnings Mobility’, U.S. Census Bureau Center for Administrative Records Research and Applications, CARRA Working Paper 2018-10.

Robinson, Joan. The Economics of Imperfect Competition, Basingstoke, UK, Palgrave Macmillan, 1933.

Russell, Tom. U.S. Steel, album Beyond St. Olav's Gate 1979-1992, 1992. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1D2Q9-1EmB4

Seegar, Pete. Homestead Strike Song, 1980, provided to YouTube by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xysm_JNnLqw

Starr, Evan (2019) ‘The Use, Abuse, and Enforceability of Non-Compete and No-Poach Agreements: A Brief Review of the Theory, Evidence and Recent Reform Efforts’, Economic Innovation Group, February 2019 Issue Brief. https://eig.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Non-Competes-2.20.19.pdf

Starr, Evan, J.J. Prescott and Norman Bushara (2021) ‘Noncompete Agreements in the US Labor Force’, The Journal of Law and Economics, 64(1).

Thornton, Robert. ‘How Joan Robinson and B. L. Hallward Named Monopsony,’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol 18, number 2, Spring 2004, pp 257–261. https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/0895330041371240

Travis, Merle Robert. Sixteen Tons, Radio Recorders Studio B in Hollywood, California, on August 8, 1946.

US Supreme Court, 17-204 Apple Inc vs Pepper, 13 May 2019, p 13. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/18pdf/17-204_bq7d.pdf

Willingham, Caius and Olugbenga Ajilore (2019) 'The Modern Company Town', Center for American Progress, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/modern-company-town/

* My thanks to the officials in the Australian Treasury's Structural Analysis Branch for invaluable assistance in preparing these remarks.