I look forward to coming here because I know this is one place where we always have a real conversation about our economy based on the facts. As serious economists, you all live in a world of facts. Where perspectives are based on evidence, where forecasts are based on the best information you have, and where your ultimate conclusions are drawn from a rigorous and methodical analysis. Today, I want to get behind some of the headline numbers, unpack some of our economic challenges and talk about how we manage them. As you know, and as I indicated a couple of months ago, the goalposts have moved pretty substantially since I spoke to you last year. Since then we have seen a sharp decline in commodity prices, coupled with a sustained high dollar – and this has had an even more substantial impact on revenue. The circumstances we face have rarely been seen in the past half century. This has required a delay in the return to surplus, to ensure we continued to support jobs and growth within our medium term fiscal strategy. So as we head into the budget period, I'd like to update you on the policy challenges facing the Australian economy. I'll also outline some of the key assets we've got in managing those challenges - our medium-term fiscal strategy and our commitment to transparency. And as always, I look forward to your questions after that.

Everyone in this room knows that over the past five years, there have been extraordinary global forces bearing down on our economy, unprecedented in magnitude.

We were virtually the only advanced economy to avoid recession, but we didn't come out of the GFC unscathed and there's no doubt we're still feeling its aftershocks. The GFC was the catalyst for long term structural changes in private spending and borrowing behaviour, and we've seen ongoing global volatility.

I've just returned from the G20 Finance Ministers' Meeting in Moscow, and while there is a sense of cautious optimism about the global recovery, there is certainly no sense of complacency about the challenges and uncertainty that remain. Nearly every major advanced economy contracted in the December quarter, the recession in Europe continued to deepen, and the recovery remains hostage to policy actions in the world's biggest economies. So the GFC and global turmoil have left a lasting imprint on parts of the Australian economy, but there have been other global forces at play. One of these has been the shift in global growth from West to East, which has seen profound changes in our economic landscape. While this shift presents enormous opportunities, it has also imposed profound structural change on our economy. We've experienced a once-in-a-century terms of trade boom, an equally unprecedented resource investment boom and a rapid and sustained appreciation of the Australian dollar. More recently, the dollar has remained stubbornly high as our terms of trade have come off and as interest rates have fallen, adding to already painful adjustments for some sectors. So we've faced some big, unusual and difficult transitions, but by almost any yardstick, we've come through it remarkably well. This is particularly evident in real economic outcomes – we've maintained solid and relatively stable growth, and low unemployment. Of course, we know that as we approach the next phase of the resources boom – the production phase – the transition to non-mining growth drivers may not be seamless.

But we approach this transition from a remarkable starting point, having avoided the permanent output loss and skills destruction that plagues other countries.

Our economy is now 13 per cent bigger than it was five years ago, while around half of the 34 advanced economies have yet to return to their pre-crisis real output levels. As everyone in this room knows, real GDP growth is a fundamental indicator of an economy's strength, reflecting the change in the volume of what we produce. But while Australia's real economic outcomes have been extraordinary, we've recently seen an unusual disconnect between the real and nominal economy. Nominal GDP is the dollar value of production– capturing both the volume of that production and the prices that are received for it.

As I said late last year, recently there's been a sharp slowing in nominal GDP growth, which has tracked below real GDP growth in the June and September quarters. In the year to the September quarter, nominal GDP grew 1.9 per cent – well below the 3.1 per cent growth in the real economy.

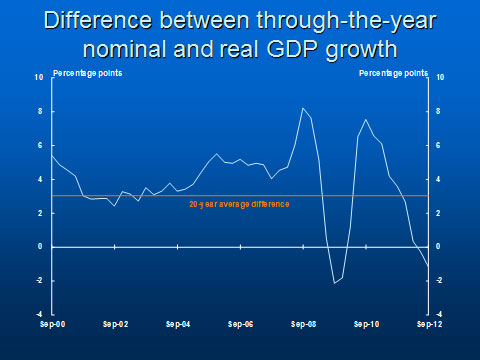

As you can see in the Chart, nominal GDP growth has historically been around 3 percentage points higher than real GDP growth, on average, in through-the-year terms – that's the orange line. However, through-the-year through to September, nominal GDP growth was more than 1 percentage point below real GDP growth.

This divergence is very rare – it's occurred for only four short periods in 53 years since the ABS began producing quarterly National Accounts. The last time nominal GDP was this weak was the global financial crisis. Before that it was the Asian financial crisis in 1998 and, before that, the Menzies government credit crunch in 1961. On all but one of those occasions, the explanation was the same: a sharp fall in global commodity prices led to a sharp decline in our terms of trade.

What is particularly striking about the current divergence is that the Australian dollar has remained high while our terms of trade have declined – something we didn't see during the GFC. This has placed pressure on the profit margins for our trade-exposed industries, and has contributed to subdued growth in domestic prices. Of course, the decline in the terms of trade was not unexpected, but I'm not aware of any reputable forecaster who predicted the pace of decline in global commodity prices, combined with virtually no change in the exchange rate. We saw iron ore prices fall around 40 per cent in the year to September while thermal coal prices fell around 30 per cent. While both have since regained some ground they are still significantly lower than 18 months ago. Despite this, the exchange rate has barely budged. Most economists also expect commodity prices to gradually moderate over time, as more low-cost supply comes on line. This means that nominal GDP growth may remain below trend even as real GDP growth remains solid. Of course in the medium term, we expect both real and nominal GDP to grow around their trend rates.

While real GDP is a fundamental indicator of economic strength, we live in the nominal economy through the prices we pay and incomes we earn. This is as true for the government as it is for individuals. So the unusual disconnect between real and nominal growth raises important issues for how we conduct fiscal policy because what predominately matters for tax revenues is nominal incomes. While the GFC was the catalyst for ripping $160 billion in revenues out of our budget, we didn't anticipate the full impact of global volatility and broader changes on our revenue base or how long they would last. We have seen a longer term hit to our revenues from the GFC, ongoing global volatility and the evolution of the mining boom through its enormous investment phase. These impacts have lasted longer than we originally expected. On top of this our revenues have taken another hit from the massive fall in commodity prices and the high dollar since I spoke to you last year. This has significantly compounded the challenges I discussed last year, and is why I have returned to this topic today. Company tax and resource rent taxes continue to be hit by combination of the high dollar, lower commodity prices and greater deductions from the investment boom - from both depreciation and other sources. Asset prices remaining below pre-GFC levels and accumulated losses continue to weigh on capital gains tax. Lower asset prices also mean lower superannuation taxes and have contributed – among other things - to more historically normal levels of household saving which itself impacts on indirect taxes.

Taxes on wages and indirect taxes are - at least in the short term - more likely to follow trends in real economic activity and have been more in line with our expectations, reflecting our solidly growing real economy. It's impossible to ignore these massive changes that have taken place in our revenue base.

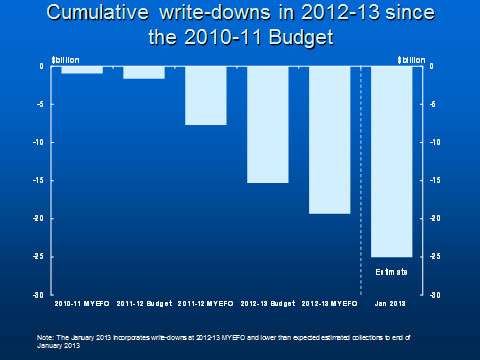

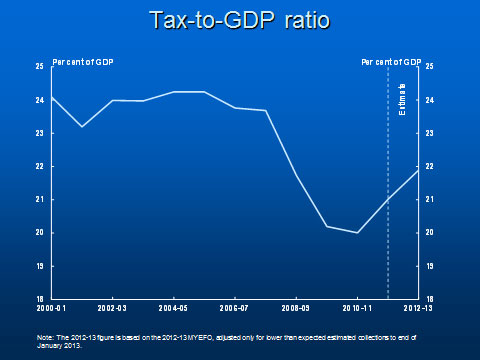

As you can see in the Chart, including further write-downs since MYEFO, expected revenue in 2012-13 has been revised down by over $25 billion since the 2010 election. The tax to GDP ratio in 2012-13 is expected to be below 22 per cent for the fifth successive year. The last occurred in the early 1990s recession, when unemployment approached 11 per cent. No government in more than 30 years has run a surplus with a tax-to-GDP ratio below 22 per cent. All of the surpluses run by the Howard Government in the 2000s had a tax-to-GDP ratio above 23 per cent – it was not spending restraint. What's worse, as the first phase of the mining boom filled their coffers, they used this one off boost to revenues to fund structural spends that undermined the structural integrity of the budget. During this period, Treasury analysis shows that taxes were revised up by $334 billion over seven years and the former government spent $314 billion of that on new policy.

Like the introduction of the PHI rebate for millionaires. Since its introduction in 1999, the private health insurance rebate has more than doubled in real terms, to be broadly comparable with what the Government spends through Medicare on GP consultations (about $5.6 billion in 2011-12). Through means testing, and changes to the rebate announced at MYEFO, we have ensured this policy is sustainable. This is one of the many measures we have undertaken to improve the structural position of the budget, but there will need to be more.

Because of the pressures hitting our revenues, I said in December that it was unlikely that the budget would return to surplus in 2012-13. In the first four months of the financial year we saw a big impact on revenues, particularly due to the rapid decline in commodity prices and the sustained high dollar. This has hit corporate profits not just in resources, but across the board. In December, I said it would not be responsible to cut further to offset the big decline in revenues, as this was likely to put jobs and growth at risk. At this time there was only six months left in 2012-13. Making the savings required to preserve the surplus in such a short space of time would have risked growth and jobs. It would be irresponsible to do so. I understand that some will say that we were slow to acknowledge that return to surplus in 2012-13 is unlikely. But as I've said, you have to make these assessments on all the facts. When we knew the fiscal outcomes for the first four months of the financial year, we were in a firm enough position to make that decision. This is not a decision that would be taken lightly by any government, but as the facts change, responsible governments also change their outlook. In the two months since I made that announcement, we have continued to see revenues underperform. Last week, the Finance Minister released the latest monthly financial statements, which showed that for the six months to the end of December, our cash receipts were $3.9 billion below what we expected at MYEFO. Early data for January suggests another $2 billion could be added to that revenue shortfall.

The MRRT - as a profits based tax – has been impacted substantially by the slump in commodity prices, but the MRRT is still only responsible for around 20 per cent of the write down in revenues. If only it had attracted just 20 per cent of the commentary. These revenue shortfalls will obviously impact beyond the current year. But we've maintained our expenditure restraint, with spending more than $1 billion below MYEFO estimates for the last six months of 2012. This means that payments remain on track to be around 23.8 per cent of GDP in 2012-13 – lower than half of the budget outcomes delivered by the Howard Government. We'll update our numbers in the Budget in under three month's time, in the usual way - but it's clear that lower revenue has been the key factor influencing our fiscal outlook.

Today I also want to outline how we'll be going about putting the budget together in light of the economic and fiscal context I've just outlined. The government remains committed to our medium term fiscal strategy that has not only guided our response to the worst global crisis in 80 years, but also our fiscal consolidation in recovery. Consistent with this strategy we won't lean against the automatic stabilisers in the near term, and we recognise the need for structural savings in the medium term to offset priority structural spending. Over the past 5 Budgets and the recent mid-year review we've put in place more than $150 billion in saves, many targeted at addressing the structural challenges in the budget. The structural savings we've already made will deliver a cumulative improvement to the budget of over a quarter of a trillion dollars by 2020-21. But we need to do more to ensure our budget is sustainable over time. Our focus will be on ensuring the sustainability of priority spending, and improving the integrity of the tax system. Inevitably, these reforms will involve very difficult decisions, but they will always be guided by our Labor values. And we will continue to offset new spending over the forwards, building on our record since the 2009-10 Budget. As the Prime Minister noted in January, it would not be responsible to announce spending without outlining long-term savings strategies which show what will be foregone in order to fund the new expenditure. On Sunday, when the government announced our plan to support innovation in our economy we also announced the savings that will pay for this. We said we would remove the R&D tax concession for large companies with a $20 billion Australian turnover or more, to ensure innovation spending is directed to where it will have the biggest benefit. This saving will also deliver benefits to the bottom line over and above funding the package – so it's a down payment on the repair that the budget needs. We'll continue to identify savings to make room for big reforms like the NDIS and the Gonski school reforms, which are also part of our investment in the five pillars of productivity. We'll continue to ensure that real spending growth averages no more than 2 per cent growth over the forward estimates – compared to around 3.7 per cent on average over the ten years before the GFC under the previous government. We'll also keep taxation as a share of GDP, on average, below the 2007-08 level of 23.7 per cent.

As you can see in the Chart, tax-to-GDP in each of our five years in government has been historically low, and in fact lower than every year of the previous Liberal Government. Make no mistake - this is a revenue, not an expenditure story. We should not forget that the Liberals were the highest taxing Government in Australia's history – tax to GDP reached its highest ever level of 24.2 per cent in 2004-05 and 2005-06. If taxes in 2012-13 were collected at that same level we'd have well over $30 billion in additional revenue - more than $3,000 extra per taxpayer.

So clearly, we're facing a challenging set of circumstances, with substantial forces at work in our economy. We need to have this conversation based on the facts, so I believe we need a greater level of transparency when it comes to the budget – and that's exactly what I'll be announcing today. It is important that we are constantly assessing the rigour of the economic and fiscal information presented in the budget. You'd all agree that no set of forecasts is perfect, and forecasting has been particularly challenging in recent times given the big global forces bearing down on our economy. To enhance its performance, Treasury Secretary Dr Martin Parkinson initiated a review of Treasury's forecasting methodology, overseen by an independent panel, led by Dr David Chessell. This report is being released today. The conclusion reached by the external panel that undertook the review was that:

"Treasury approaches the forecasting task in a very professional manner and the forecasts it generates are broadly as accurate as those of both domestic forecasters and those generated by comparable agencies in countries with similar institutional arrangements as Australia".

In addition to confirming Treasury's strong forecasting record, the external panel also recommended areas where Treasury's forecasting processes can be enhanced.

Treasury will take on these recommendations in full and will improve the accuracy and transparency of the budget numbers. I'd like to congratulate Dr Chessell and the external panel he led for a comprehensive report. I am also announcing a number of measures to increase transparency in light of this being an election year.

I'm proud that we have established the Parliamentary Budget Office and today I'm announcing we'll enhance its capacity to ensure budget transparency from all sides of politics, with additional funding to the PBO. This will enhance the capacity for costings to be prepared in the lead up to the election, removing any excuse for policies to be released like thought balloons rather than rigorously costed policies. Transparency would be further enhanced if the PBO were to prepare a post-election audit of all political parties, publishing full costings of their election commitments and their budget bottom line 30 days after an election. We will introduce legislation for consideration by the Parliament to enable this reform. This will remove the capacity of any political party to try to mislead the Australian people and punish those that do. It will avoid a situation we saw last election, where the Liberal Party thought they could con the Australian people.

As a result of the reforms I am announcing their $11 billion black hole in the budget bottom line would have been uncovered regardless of the election outcome.

I also commit to release the 2012-13 preliminary underlying cash balance outcome when the Secretaries of Treasury and Finance inform the Government that they have a reliable figure. Treasury and Finance officials last week were clear that a reliable estimate of the underlying cash balance could be made well before the election and we commit to releasing it. This means that the 2012-13 outcome of the underlying cash balance – the most important budget aggregate - will be there for everyone to see. There will be no fiscal surprises after the election.

The Australian economy has been through one of the toughest periods in our history over the past 5 years. The fact that we avoided recession, kept people in work, and have been able to convert our success into a mining investment boom speaks volumes about our economic strength. But we have not been immune from the forces at play in the global economy and that has had a huge impact on our budget. These are the facts, so they should be the starting point for our political debate.

That is why today I have outlined a range of important measures to enhance transparency in our economic and political debate. I welcome a contest of ideas. That's what elections should be about and it's a key reason I got into politics. It's why the Prime Minister announced the election will be held on 14th September – so we can have the discussion about each party's plans for the future, and most importantly, how each party is going to pay for them. But while you can choose your own policy arguments, you can't choose your own facts. And I look forward to continuing this discussion by taking your questions.